HEART DEFECTS

Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect. Defects that involve the wall or vessels of the heart include atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). In certain situations, guidelines recommend surgery or transcatheter device closure to repair the defect and prevent complications.1

With over 20 years of demonstrated clinical experience, the Amplatzer™ Septal Occluder is the standard of care for minimally invasive atrial septal defect (ASD) closure, with a variety of sizes and features that facilitate precise placement.

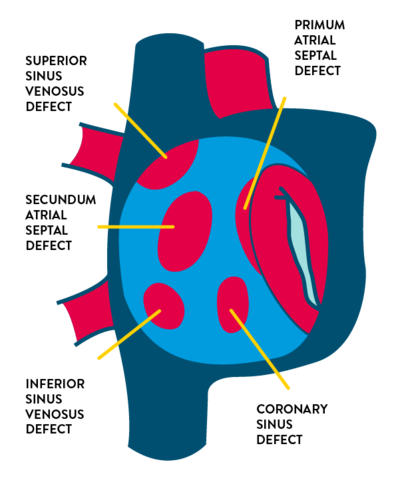

- Secundum ASD (75% of cases) in the region of the fossa ovalis

- Primum ASD (15% to 20%) located inferiorly near the crux of the heart

- Sinus venosus ASD (5% to 10%) located near:

- Superior vena cava entry

- Inferior vena cava entry

- Coronary sinus defect (less than 1%) which causes shunting through the coronary sinus ostium

About 65%-70% of patients with a secundum defect are female.2

Most such defects have no identifiable cause, but certain genetic abnormalities have been linked to ASDs. The risk of a secundum defect in particular is increased in families with a history of congenital heart disease—particularly when ASD has also been diagnosed in a sibling.2

ASDs have been associated with maternal characteristics and behaviors such as2:

- Fetal alcohol syndrome

- Cigarette smoking, particularly in the first trimester

- Advanced maternal age (≥ 35)

- Certain antidepressant use

- Diabetes

When symptoms develop

Most children with isolated ASDs are asymptomatic. If patients are untreated, however, symptoms can occur in adulthood.2

Symptoms of atrial septal defect

The consequence of a left-to-right shunt across an ASD is right ventricular volume overload and pulmonary over-circulation. Patients who have large atrial shunts can experience symptoms related to excess pulmonary blood flow and right-sided heart failure. In infants, children, and young adults up to approximately age 20, symptoms may include:

- Heart murmur (followed up with echocardiogram)

- Frequent respiratory infections

- Slow weight gain

In older adults ASDs may present with symptoms of:

- Dyspnea

- Palpitations

- Fatigue and exercise intolerance

- Cyanosis

- Atrial arrhythmias—atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, and sick sinus syndrome

- Peripheral edema

- Cardiomegaly on routine chest x-ray

- More audible murmur during pregnancy

- Paradoxical embolism

Symptoms in patients with small ASD

Patients who have small defects (< 10 mm) have minimal to no enlargement of the right heart structures, and these patients can remain asymptomatic into their 40s or 50s. But even these patients may develop symptoms with increasing age. Symptoms appear over time for several reasons—in 18% of cases because of an increase in the size of the defect (although this is more likely to occur in those who initially have larger defects).2 Increased shunting can also be a factor, caused by a decrease in left ventricular (LV) compliance as the patient develops coronary artery disease, hypertension, or acquired valvular disease.

TO AVOID LATE DIAGNOSIS: AWARENESS OF GRADUAL ONSET OF SYMPTOMS

Because many patients experience the gradual onset of symptoms—and may exhibit only subtle physical findings—late diagnosis can occur in patients with ASDs. Proper attention to symptom presentation can preclude late diagnosis, which puts patient at higher risk for arrhythmias, pulmonary arterial hypertension, LV systolic dysfunction, and paradoxical embolism.

Diagnostic evaluation

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the primary imaging modality for an ASD. Clinicians should visualize the entire atrial septum, from the orifice of the superior vena cava to the orifice of the inferior vena cava using multiple views. This is important given that poor quality transthoracic images can produce false-negative diagnoses, which can be relatively common.

TV

- Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;000:e000-e000. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

- Geva T, et al. Atrial septal defects. Lancet. 2014;383:1921-1932.

- Adler DH. Atrial septal defect. Medscape. emedicine.medscape.com/article/162914-workup.

- Shuler CO, et al. Prevalence of treatment, risk factors, and management of atrial septal defects in a pediatric Medicaid cohort. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(7):1723-1728. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0705-5.

- Nyboe C, et al. Long-term mortality in patients with atrial septal defect: a nationwide cohort-study. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:993-998. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx687.

- Kashour TS, et al. Successful percutaneous closure of a secundum atrial septal defect through femoral approach in a patient with interrupted inferior vena cava. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:620–623.

- Stout KK, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;000:e000-e000. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603.